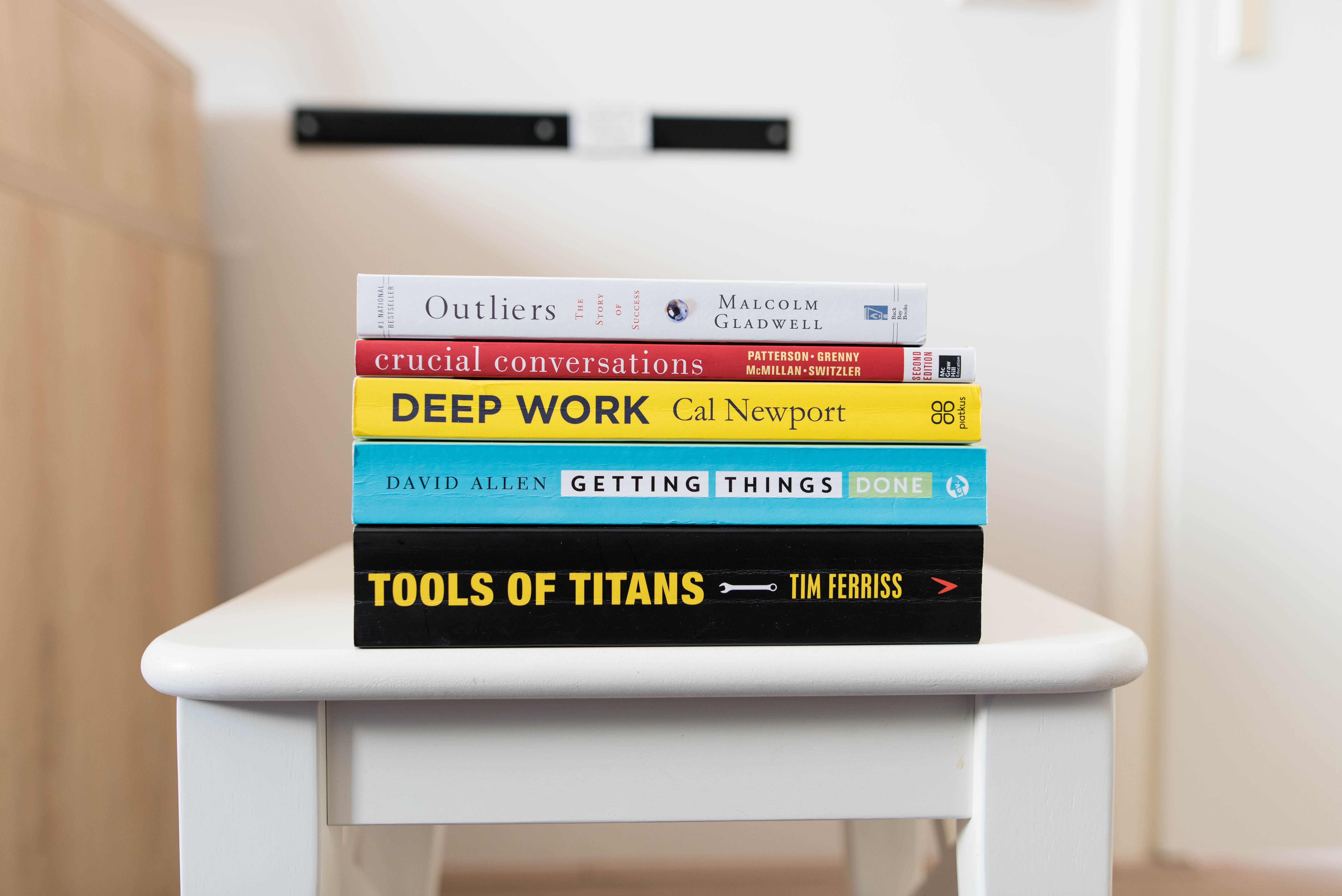

5 Lessons from Cal Newport’s “Deep Work”

Cal Newport's 2016 book, Deep Work, is a masterpiece of digital minimalism. Here are 5 important lessons from this landmark book on focus, productivity and mindfulness.

Steven Puri

Save time with Sukha

Deep Work

In 2016, Georgetown computer science professor Cal Newport coined the term, “Deep Work,” in his book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Newport is the antithesis of the social media age: he doesn’t use social media and only checks email once a day.

In fact, this digital minimalist’s recent book A World Without Email argues that humans are not built for digital communication at all. Newport envisions a world in which unnecessary communication is minimized, replaced by clear processes and goals that maximize everyone’s time—and in the process helps us get off of our devices.

In his book, he offers a definition:

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.

The opposite dominates in the digital age:

Shallow Work: Non-cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

Below are five lessons from Deep Work. Five years since publication, Newport's landmark book remains as relevant as ever.

Use It or Lose It—so Use It

We’ve all heard the former collegiate star athlete reminisce about their physical prowess "back in the day." While our bodies break down as we age, continued exercise and good nutrition keep us healthy long into old age—the 108-year-old marathon runner; the 72-year-old deadlifting 520 pounds.

The same holds true with attention. As Newport writes, when you spend too much time in “a state of frenetic shallowness,” you risk permanently losing the ability to focus on anything. “Use it or lose it” is as true with our minds as our bodies.

That means you have to exercise your brain as often as your body. And that means turning off your notifications and refusing to check social media so that you can focus on the task in front of you..

Busyness Is Not Productivity

Doing lots of stuff doesn't necessarily mean you’re being productive. Every job needs clear indicators for performance. Otherwise, you’re just swimming upstream with no idea where you’re actually supposed to arrive.

Newport gives the example of former Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer banning work from home measures in 2013. The reason? Remote workers weren’t logging into the servers enough.

As Newport points out, what Mayer was effectively arguing was that they weren’t checking email enough—the exact opposite of actually being productive. Mayer stated that she needed to see her workers “visibly busy.”

By contrast, Newport argues,

Knowledge work is not an assembly line, and extracting value from information is an activity that’s often at odds with busyness, not supported by it.

Deep work doesn’t have to be public and flashy. Sometimes the slow and steady pace of a focused individual drives industries forward, not checking your email every 20 minutes.

Treat Work Like a Craft

Whether you’re a marketer, lawyer, consultant, writer—whatever career you’ve chosen—make it a craft. Skillful means can be applied to any vocation.

If you treat your job like a craftsman, Newport writes, “then like the skilled wheelwright you can generate meaning in the daily efforts of your professional life.”

Newport notes that the “follow your passion” ideology is flawed. Career satisfaction does not come by checking off every box on an ideal list. Aspiration is great, but if you treat every job as a craftsman, your attention and focus are fully committed to the task at hand.

That’s a skill you’ll take with you wherever you go.

A wooden wheel is not noble, but its shaping can be.

Willpower Is a Finite Resource

Every day, you wake up with a finite amount of willpower. This is why people tend to make poor eating decisions at night—carbohydrate-rich comfort foods are more appealing to the tired mind when it’s harder to resist temptation.

To make the most of your daily allotment of willpower, Newport advises implementing habits that exploit your brain’s most focused time to do Deep Work. As he writes,

The key to developing a deep work habit is to move beyond good intentions and add routines and rituals to your working life designed to minimize the amount of your limited willpower necessary to transition into and maintain a state of unbroken concentration.

The first step, he continues, is to schedule Deep Work into your calendar. Then, stick to it.

Embrace Boredom

This might be the hardest lesson for the social media age, which also makes it the most valuable. Smartphones have given us the ability to never be bored.

The trade-off? We’re always distracted.

If every moment of potential boredom in your life—say, having to wait five minutes in line or sit alone in a restaurant until a friend arrives—is relieved with a quick glance at your smartphone, then your brain has likely been rewired to a point where it’s not ready for deep work—even if you regularly schedule time to practice this concentration.

Staring aimlessly into space is not a worthless endeavor. Consider it recharging.

Of course, boredom is not a replacement for your focus time. Balance is necessary.

But as Newport details, constantly checking your phone at any hint of boredom prepares your mind to never focus. And that cost is way too high when a few minutes of doing nothing is available to everyone.